Is Jevic Hauling a Surprise for 363 Sales that Include Priority-Skipping Distributions?

Prior to the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Czyewski v. Jevic Holding Corp., 137 S.Ct. 973, 197 L.Ed.2d 398 (2017), one way to reshuffle the deck chairs on the titanic in a case with too little money, no more assets and too many creditors was for the parties to divvy up the remains through a structured dismissal under Section 349 of the Bankruptcy Code. Often such structured dismissals involved a secured lender allowing some of its collateral to be used to pay off other creditor groups in order to get consensus around dismissing the case, though not necessarily in accord with the priority rules set forth in the Bankruptcy Code. See 11 U.S.C. §§ 726(a)(2); 1122(a); 1123(a)(4); 1129(a)(7)(A)(ii). That is, under these structured dismissals, one group of creditors received a distribution while creditors holding claims of equal priority received less or nothing at all. Jevic put an end to priority-skipping structured dismissals.

The Jevic decision does not necessarily apply to distributions other than those effectuated through a structured dismissal. Indeed, in dicta, the Supreme Court noted that there may be situations in which priority-skipping distributions may be appropriate, specifically pointing to “‘first-day’ wage orders that allow payment of employees’ prepetition wages, ‘critical vendor’ orders that allow payment of essential suppliers’ prepetition invoices, and ‘roll-ups’ that allow lenders who continue financing the debtor to be paid first on their prepetition claims.” 137 S.Ct. at 985 (citations omitted). The Supreme Court described these exceptions as representing a “significant offsetting bankruptcy-related justification.” Id. (emphasis supplied). The Jevic court contrasted an improper structured dismissal containing priority-skipping final distribution of a debtor’s assets from these exceptions because “it does not preserve the debtor as a going concern; it does not make the disfavored creditors better off; it does not promote the possibility of a confirmable plan; it does not help to restore the status quo ante; and it does not protect reliance interests.” Id. at 986.

Given that 363 sales—frequently followed by dismissal or conversion—are often the fate of chapter 11 debtors who also find themselves with too little money, few assets and too many creditors, one might ask whether Jevic applies to Section 363 sales. That is, may debtors, secured creditors and consenting parties accomplish through the distribution of sale proceeds in an asset purchase agreement what they cannot accomplish through a structured dismissal? Early indications are that courts and disfavored creditors may read Jevic’s admonition against structured dismissals as applying to priority-skipping sales distributions as well, unless the sale proponents can articulate a “significant offsetting bankruptcy-related justification” for the distribution.

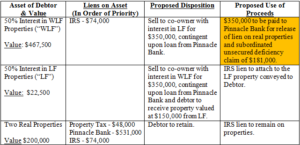

In the first, and most readily applicable, case on point, Bankruptcy Judge Shelley Rucker held that, under Jevic, a debtor could not distribute the proceeds from a 363 sale through a settlement agreement that resulted in priority-skipping. See In re Fryar, 570 B.R. 602, 609-10 (Bankr. E.D. Tenn. 2017). The complicated settlement proposed by the debtor in Fryar is explained in the following chart, with the problematic portion of the proposal highlighted in yellow. See id. at 605-06.

Creditors holding approximately $436,000 of unsecured claims and the U.S. Trustee objected to the proposed sale and settlement, arguing that Pinnacle was being preferred and the priorities under the Bankruptcy Code were being reordered for Pinnacle. Id. at 605. The Bankruptcy Court agreed. The proposed transaction resulted in Pinnacle Bank receiving all of the value from the sale of the Debtors’ interest in WLF, despite Pinnacle Bank having no lien on that interest, while the IRS, which had a first priority lien of $74,000 on that interest, was not being paid from the sale proceeds. Moreover, Pinnacle’s unsecured deficiency claim on the loan secured only by the two properties was being reduced from $391,000 to just $181,000. Id. at 606, n.3.

Judge Rucker concluded that the proposed sale of the debtor’s assets appeared to reflect the proper exercise of the debtor’s business judgment. Id. at 607. However, “because the business terms of the sale also involve[d] a settlement and a payment of one unsecured creditor ahead of other prior parties and other unsecured creditors” the court had to separately determine whether the settlement could be approved. Id. Judge Rucker first noted that the settlement clearly contemplated Pinnacle Bank “moving to the head of the line” in violation of the Bankruptcy Code’s priority scheme. Id. at 609. She then distinguished the situation before her from those alluded to by the Jevic court as situations involving a “significant offsetting bankruptcy-related justification.” Id. Rather, the “settlement [was] more of a preamble to a conversion or structured dismissal than it [was] to” a reorganization. Id. at 610.

Judge Rucker went on to admonish that parties seeking to make distributions in a priority-skipping manner as part of a settlement must articulate a significant offsetting bankruptcy-related justification for doing so:

In light of the Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Jevic, parties who seek approval of settlements that provide for a distribution in a manner contrary to the Code’s priority scheme should be prepared to prove that the settlement is not only “fair and equitable” based on the factors to be considered [within the Sixth Circuit under Bauer v. Commerce Union Bank, Clarksville, Tenn., 859 F.2d 438, 441 (6th Cir. 1988)], but also that any deviation from the priority scheme for a portion of the assets is justified because it serves a significant Code-related objective. The proposed settlement should state that objective, such as enabling a successful reorganization or permitting a business debtor to reorganize and restructure its debt in order to revive the business and maximize the value of the estate. The proposed settlement should state how it furthers that objective and should demonstrate that it makes even the disfavored creditors better off.

Id. at 610 (emphasis supplied).

The Tenth Circuit Bankruptcy Appellate Panel recently mentioned Jevic in affirming a bankruptcy court’s decision denying a trustee and his counsel compensation for, among other things, negotiating a carve-out with a secured lender for the benefit of unsecured creditors in derogation of the debtor’s homestead exemption. See Jubber v. Bird (In re Bird), 577 B.R. 365 (10th Cir. B.A.P. 2017). In Bird, the same trustee was appointed to administer two chapter 7 cases filed by individuals. In each case the debtor or debtors owned residential real property that, based on the debtors’ schedules, was fully encumbered, including by IRS tax liens. Despite the fact that the estate had no equity in the properties, the trustee and his counsel objected to the debtors’ homestead exemptions, hired a realtor and sought to sell the properties. The bankruptcy court overruled the trustee’s homestead objections, and the trustee took an appeal from those orders. The trustee also entered into a stipulation with the IRS in each case allowing for a $10,000 “carve-out” from the IRS’s lien for the benefit of unsecured creditors. The debtors, on the other hand, sought to have the trustee abandon the properties and then converted their cases to chapter 13 cases to prevent the trustee from selling the homes and disregarding their homestead exemptions. The conversion mooted the trustee’s motion to sell the properties.

The trustee and his counsel then filed fee applications in each case, including legal fees of $31,110.97 in one case and $28,998.63 in the other, and sought to have those fees treated as an administrative expense in the debtors’ chapter 13 cases. The bankruptcy court denied the trustee or his counsel any compensation whatsoever in both cases, finding that the fees had not been incurred to provide any benefit to the estate. The bankruptcy court found that the trustee’s effort to avoid the homestead exemption was pointless, the trustee did not need to bother negotiating a carve-out with the IRS regarding fully-encumbered property subject to a homestead exemption, and that the sale motion could never have been approved under Section 363(f), among other conclusions justifying denial of all of the requested compensation.

On appeal, the B.A.P. affirmed in full. One of the trustee’s arguments on appeal was that he had benefitted the debtors’ estates by negotiating the carve-out with the IRS. The B.A.P. disagreed. The court noted that trustees may, under some circumstances, retain fully encumbered property in the estate and seek to sell it if they can obtain a carve-out that will provide a meaningful distribution to creditors. Id. at 378. Here, however, the carve-out accomplished little for the debtors’ creditors, resulted in substantial legal fees far in excess of the benefit obtained, and harmed the debtors by not only stripping them of their homestead exemption but taking their homes as well. Id. at 379. And, the B.A.P. noted, that while Jevic may not preclude all carve-outs from a secured creditor’s collateral, “Jevic stands for the proposition that neither the parties, nor the courts, are free to circumvent the Bankruptcy Code’s rules and policies regarding priorities and distributions through manipulation of substantive and procedural protections.” Id. at 379, n.65 (citing Jevic, 137 S.Ct. at 986-87; emphasis supplied).

In another recent case, a disappointed competing bidder appealed a bankruptcy court’s order approving a sale under Section 363 of the Bankruptcy Code by arguing, among other things, that the order had violated Jevic because the buyer had assumed certain liabilities while not assuming the debtor’s obligations to creditors holding claims of equal priority. In re Old Cold LLC, 2018 WL 387619, at *10 (1st Cir. Jan. 12, 2018). The debtor argued that Jevic does not apply to Section 363 sales at all, because such sales “involve potentially ‘offsetting bankruptcy-related justifications.’” Id. (quoting Jevic, 137 S.Ct. at 986). The First Circuit declined to rule on the issue at all because it held that the sale could not be challenged on a substantive ground under Section 363(m) of the Bankruptcy Code, which provides that a sale cannot be undone, even if the order approving the sale is later reversed, if the buyer purchased the property in good faith and the order approving the sale is not stayed. Id. at *11. The First Circuit rejected the appellant’s good faith arguments (id. at *7-10) and there was no stay of the sale order pending appeal.

Finally, another case of note, albeit not directly involving a 363 sale, is Bankruptcy Judge Kendig’s decision in In re Briar Hill Foods, LLC, 2017 WL 4404274 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio Sep. 29, 2017). In Briar Hill, a receiver had been appointed by the debtor’s secured lender prior to the bankruptcy case and the receiver took possession of the debtor’s real property. A chapter 11 case was filed to facilitate the sale of the debtor’s property. However, relying on Section 543(d) of the Bankruptcy Code, the secured lender sought to have the receiver retain and manage the properties, rather than having the properties turned back over to the debtor as required under Section 543(b)(1) of the Bankruptcy Code. Judge Kendig was not willing to approve the motion because he felt that the receiver’s continued management of the properties was inconsistent with the notion of the debtor being the debtor-in-possession under chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code and the Bankruptcy Code’s prohibition against the appointment of receivers under Section 105(b). In the end, Judge Kendig invoked Jevic and noted that the “court cannot concoct procedures and rules to accommodate a good result, especially when the means circumvent the Bankruptcy Code.” Id. at *2.

At a minimum, Judge Rucker’s decision in Fryar and the debtor’s position in Old Cold LLC indicate that courts and parties should be attuned to the need to identify a “significant offsetting bankruptcy-related justification” if they are going to propose a priority-skipping distribution of sale proceeds. The references to preserving the debtor as a going concern and advancing the possibility of confirming a plan in Jevic give the proponents of sales that include priority-skipping a crutch to lean upon. At a minimum, sales that incorporate the payment of obligations to vendors or customers with whom the buyer wishes to retain relationships may fall within the dicta contained in Jevic. But practitioners should be warned that those proposing a priority-skipping distribution as part of a Section 363 sale with little merit other than the promise of a “good result” may find themselves on the wrong side of Jevic.

As the law continues to evolve on these matters, please note that this article is current as of date and time of publication and may not reflect subsequent developments. The content and interpretation of the issues addressed herein is subject to change. Cole Schotz P.C. disclaims any and all liability with respect to actions taken or not taken based on any or all of the contents of this publication to the fullest extent permitted by law. This is for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal advice or create an attorney-client relationship. Do not act or refrain from acting upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining legal, financial and tax advice. For further information, please do not hesitate to reach out to your firm contact or to any of the attorneys listed in this publication.

Join Our Mailing List

Stay up to date with the latest insights, events, and more